Describing sounds¶

Recall last week’s discussion about the differences between hearing and listening. This week, will focus on how we listen, what we listen to, and how we can describe sound and reflect on its meaning.

Different sound analysis approaches¶

Academic approaches to describing sound vary across the three main directions we are considering in this course (musicology, psychology, and technology). They each tap into various subfields (or paradigms), each offering distinct frameworks and terminologies:

Acoustics focuses on the physical properties of sound waves, such as frequency, amplitude, duration, and propagation in different media. An acoustician might describe a clap in a concert hall as “a broadband impulse with a peak amplitude of 85 dB SPL, followed by a reverberation decay time of 1.8 seconds,” using measurements and graphs to illustrate how sound behaves in the space.

Psychoacoustics investigates how humans perceive sound, using quantitative measures (frequency, loudness, spatial location) and perceptual attributes (brightness, roughness, etc.). A psychoacoustic study might report that “a 1000 Hz tone at 60 dB SPL is perceived as moderately loud and bright,” and compare listener responses to tones with varying roughness or spatial placement.

Music theory: focuses on musical parameters (pitch, rhythm, timbre, dynamics) and cultural context. A musicologist might describe a violin tone as “a slightly sharp C, with a bright timbre, starting from pianissimo and with a gradual crescendo,” using musical notation to visualise it on paper.

Spectromorphology is a specialised form of music theory that analyses the spectral (frequency) and morphological (shape and evolution) characteristics of sounds. A spectromorphological analysis could describe a cymbal crash as “an impulsive onset followed by a complex, evolving spectrum that decays over several seconds,” visualised with a spectrogram showing frequency content over time.

All of these approaches focus specifically on describing the sound “itself”. However, different disciplines also consider other factors in their analyses.

Fields studying sound¶

Numerous fields study the effects of sound on people or environments:

Sound studies is an interdisciplinary field that examines sound as a cultural, social, and material phenomenon. It draws on media studies, anthropology, history, and philosophy to explore how sound shapes and is shaped by society, technology, and everyday life. A sound studies scholar might analyse how urban noise regulations reflect social attitudes toward public space, or investigate the role of sound in shaping collective memory and identity.

Acoustic ecology emphasises environmental context, categorising sounds as, for example, keynotes, signals, or soundmarks. Soundscapes are described in terms of their ecological function and impact. An acoustic ecologist could document a city park by noting “birdsong as a keynote, a distant siren as a signal, and the hourly chime of a church bell as a soundmark,” analysing how each sound shapes the experience of the space.

Ethnography is a subbranch of anthropology and uses qualitative methods such as interviews, field notes, and participatory observation to describe how communities interact with and interpret their sonic environments An ethnographer might record that “residents describe the evening call to prayer as calming and unifying,” supplementing this with field notes and interviews about its social significance.

Linguistics and semiotics examine the meaning and communicative function of sounds, including onomatopoeia, prosody, and sound symbolism. A linguist could analyse the word “buzz” as onomatopoeic, noting how its sound mimics the noise of a bee, or study how rising intonation in speech signals a question.

There is no right or wrong when it comes to studying sound. All of these approaches (and more) aim to uncover various aspects of both the physical properties of sounds but also their meaning, context, and impact on listeners. Several of them are also used in multiple combinations. We won’t have time to cover all of these in detail in this course, but we will look more closely at some of the closest ones to the fields of music psychology and technology. In particular, we will focus on two main concepts that have been influential in the development of our understanding of listening: soundscapes and sound objects.

Soundscapes¶

A soundscape refers to the acoustic environment as perceived or experienced by people, encompassing all the sounds that arise from both natural and human-made sources. Describing soundscapes involves several dimensions:

Physical properties: Documenting the types of sounds present (e.g., birdsong, traffic, water), their frequency ranges, loudness, and temporal patterns.

Ecological function: Identifying the roles sounds play in the environment, such as signalling, masking, or providing information about ecological health.

Spatial characteristics: Noting how sounds are distributed in space: directionality, distance, and reverberation within the environment.

Perceptual attributes: Describing how listeners experience the soundscape: pleasantness, annoyance, tranquillity, or stimulation.

A description of a soundscape often combines “objective” measurements, such as sound level measurements and field recordings, to create spectrograms with annotated sound maps and written descriptions, thereby capturing and analysing soundscapes. Together, these objective measurements, subjective impressions, and contextual information provide a holistic understanding of the sonic environment.

R. Murray Schafer and acoustic ecology¶

R. Murray Schafer (1933–2021) was one of the pioneers of soundscape studies. He was the one to propose and define the term soundscape as the acoustic environment as perceived by humans. Starting in the 1960s, he led the World Soundscape Project at Simon Fraser University in Canada, a groundbreaking research initiative that studied, documented, and analysed the sonic environments of various locations. Through this work, Schafer and his team developed new methods for field recording, sound mapping, and acoustic analysis, aiming to understand how sounds shape our experience of place and community.

Schafer’s most famous book is The Tuning of the World, which introduced key concepts for analyzing soundscapes:

Keynote sounds are background sounds that are fundamental to a particular environment, often heard unconsciously. Examples include the hum of city traffic or the rustling of leaves in a forest. Keynotes set the acoustic context but are not usually the focus of attention.

Signals are foreground sounds that are listened to consciously because they carry specific information or meaning. Examples include a ringing phone, a siren, or a bird call. Signals stand out from the background and often prompt a response or action.

Soundmarks are unique or characteristic sounds that are especially valued by a community or location, similar to landmarks in the visual environment. Examples might be the chimes of a local church bell, a distinctive factory whistle, or a waterfall. Soundmarks help define a place’s identity and are often preserved or celebrated.

Schafer’s work laid the foundation for the field of acoustic ecology and inspired similar projects worldwide, encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration between musicians, scientists, urban planners, and environmentalists. The project advocated for the preservation of valuable soundscapes and raised awareness about the impact of noise pollution and urbanisation on our acoustic environment. It also inspired the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology (WFAE) Conference, an international gathering bringing together researchers, artists, educators, and practitioners to explore the relationship between humans and their sonic environments.

Schafer also introduced the term schizophonia to describe the separation of a sound from its source, often through recording technology. For example, when you hear a bird song played from a speaker, the sound is no longer coming from the bird itself, but from a device. This separation can change how we experience and relate to sounds, sometimes making them feel less “authentic” or connected to their natural context.

Hildegard Westerkamp and soundwalking¶

Hildegard Westerkamp (1946–) worked with Schafer in the World Soundscape Project and is famous for developing soundwalking as a reflective practice of walking and listening to the environment. This is not only a practice of listening but also a way of engaging with the environment mindfully and reflectively. It encourages participants to become aware of the acoustic ecology of their surroundings, fostering a deeper connection to place and community. Soundwalking can be used as a tool for artistic inspiration, environmental awareness, and even therapeutic purposes.

Key aspects of soundwalking include:

Active listening: Paying close attention to the layers of sound in the environment, from the most prominent to the subtle.

Contextual awareness: Understanding how sounds interact with the physical and social context of a space.

Documentation: Participants may choose to record sounds, take notes, or create maps to capture their auditory experience.

Westerkamp’s soundwalking practice bridges both scientific research and artistic exploration. In her scientific work, Westerkamp used soundwalks to gather data on urban and natural soundscapes. Participants documented their listening experiences, helping researchers analyse acoustic environments, identify sources of noise pollution, and understand how people perceive and interact with their sonic surroundings. These soundwalks have contributed to studies in acoustic ecology, urban planning, and environmental psychology.

Artistically, Westerkamp transformed soundwalking into a creative process. She has composed works based on field recordings and reflections gathered during soundwalks, such as her acclaimed piece Kits Beach Soundwalk. Her compositions often blend environmental sounds with narration, inviting listeners to experience places through attentive listening. She demonstrated how attentive listening can deepen our understanding of environments, foster community awareness, and inspire new forms of sonic art.

Hildegard Westerkamp’s use of the term “music-as-environment” frames everyday acoustic surroundings as legitimate musical material: the city, the shore, or a forest are heard as dynamic, layered soundings rather than passive backdrops. Through practices like soundwalking she encourages sustained, analytical listening that foregrounds relationships, textures, and temporal patterns in the world, treating listening itself as a creative and ecological act. This view blurs the roles of composer, performer, and audience, suggesting that attentive engagement with environmental sounds can reveal social, cultural, and ecological meanings and become the basis for artistic and communal practice.

Steven Feld and acoustemology¶

Steven Feld (1949–) is an ethnomusicologist known for his pioneering work on the relationship between sound, culture, and perception. Feld introduced the concept of acoustemology—a blend of “acoustics” and “epistemology”—to describe how knowledge and experience are shaped through sound and listening.

Acoustemology emphasises that listening is not just a sensory act but a way of knowing and engaging with the world. Feld’s research, particularly with the Kaluli people of Papua New Guinea, demonstrated how sound is deeply embedded in social life, memory, and identity. He explored how environmental sounds, music, and language are interconnected, and how communities use sound to make sense of their surroundings.

Key aspects of acoustemology include understanding sound as a primary medium for learning, communication, and relating to place. Feld argues that listening practices are shaped by cultural context, history, and environment, and communities define themselves and their spaces through distinctive soundscapes and musical traditions. His work encourages researchers and listeners to consider how sound shapes experience and meaning, and to use listening as a method for understanding both local and global cultures.

Sound objects¶

After considering soundscapes more broadly, let us “zoom in” to investigate specific sonic events in more detail. While soundscape studies developed in Canada in the 1970s and beyond, they were greatly inspired by the French “school” of composers and theorists working in Paris in the 1950s.

Pierre Schaeffer and the Sound Object¶

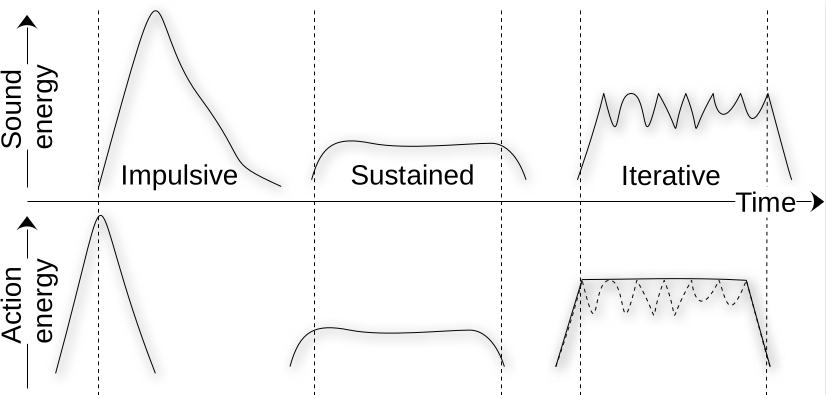

The concept of sound object—l’objet sonore in French—was proposed by the French composer and musicologist Pierre Schaeffer (1910–1995). He argued that when we listen to sound, we do not hear a continuous sound, but rather our perception is grouped into a series of separate sound objects with specific properties. For example, when we perceive speech, we hear words, not single phonemes. Similarly, when we hear music, we hear tones and short phrases that fuse into “chunks” of sound, typically in the range of 0.5 to 5 seconds (Godøy et al. 2010). These sound objects can be divided into three core types:

Impulsive: Short, percussive sounds (e.g., a click or a drum hit).

Sustained: Continuous sounds with steady qualities (e.g., a drone or a held note).

Iterative: Rapidly repeating sounds (e.g., a tremolo or a rattling noise).

These categories are part of a large spectromorphology that can be used to describe any type of sound.

An illustration of Schaeffer’s three sound types (Jensenius, 2022).

Schaeffer’s work bridged creative practice and systematic inquiry, inspiring generations of composers, theorists, and researchers. His methods combined careful listening, detailed description, and technical manipulation of recorded sound, an approach that opened new avenues for both artistic exploration and acoustic research.

He is widely credited as the originator of musique concrète, an approach developed in the 1940s–50s that treats recorded environmental and instrumental sounds as compositional raw material. Early practitioners used tape editing, splicing, speed changes, and looping to transform found sounds into musical structures, foregrounding timbre, texture, and temporal form over traditional notation.

Schaeffer’s ideas also helped establish electroacoustic music more broadly, encompassing any practice that uses electronic technology for sound generation, processing, and spatialisation. Electroacoustic work ranges from tape pieces and live electronic performance to computer music and immersive multi-channel installations, all emphasising crafting sound itself as the primary material.

His approach to “reduced listening” gave rise to acousmatic practice: listening to sounds divorced from visible causes. Acousmatic concerts (often presented over loudspeaker arrays, sometimes in darkness) emphasise the perceptual and morphological properties of sounds, inviting listeners to attend to spectral content, envelope, and movement.

Schaeffer’s legacy extends beyond composition: his taxonomy of sound objects and his listening exercises inform analysis, sound design, auditory cognition studies, and pedagogy. Techniques such as tape montage, close spectromorphological listening, and the deliberate manipulation of source–signal relations remain central tools for contemporary practice and research.

Expanding Schaeffer’s thinking¶

Several theorists have built upon Pierre Schaeffer’s foundational ideas about sound objects and listening:

Dennis Smalley (1946–, University of London) formalised the concept of spectromorphology, providing a comprehensive vocabulary for describing the spectral and morphological evolution of sounds. Smalley’s approach is widely used in electroacoustic music analysis and has helped clarify how listeners perceive the shape and transformation of sound objects over time.

Lasse Thoresen (1949–, Norwegian Academy of Music) has expanded spectromorphological analysis, creating practical frameworks for describing and notating sound objects in both electroacoustic and acoustic music. Thoresen’s work bridges theory and practice, making Schaeffer’s taxonomy accessible for composers and analysts.

Rolf Inge Godøy (1955–, University of Oslo) has advanced Schaeffer’s concepts by developing detailed models for how listeners perceive and mentally represent sound objects. Godøy’s work emphasises gestural-sonorous objects, linking sound perception to physical gestures and movement, and has contributed to the field of embodied music cognition.

Michel Chion (1947–) has introduced the concept of synchresis to describe the perceptual phenomenon where a sound and a visual event are perceived as co-occurring, even if they are artificially synchronised. This concept is central to audiovisual theory, as it highlights the human tendency to create a cohesive relationship between what is seen and heard. Synchresis plays a crucial role in film sound design, enhancing the emotional and narrative impact of scenes by aligning specific sounds with visual actions, regardless of their source.

Artistic explorations¶

As the overview above shows, the development of soundscapes and sound object theory has been driven by researchers who identify as both artists and scientists, producing both artistic and scientific results. This may be uncommon in some fields, but in sound and music, theoretical development can be seen as emerging from creative practice, and artistic practice has been inspired by theoretical development. Here, we will look at some influential artworks that have been part of the same development.

John Cage and 4’33’’¶

John Cage (1912–1992) was an American composer and music theorist whose work challenged traditional notions of sound and music. One of his most influential and controversial pieces is 4’33’', composed in 1952. The piece consists of three movements, during which the performer is instructed not to play their instrument. Instead, the focus shifts to the ambient sounds of the environment, making the audience’s listening experience the central element of the composition. Cage’s work emphasises the idea that silence is never truly silent. The piece invites listeners to engage deeply with the sounds around them, blurring the line between music and environmental noise. 4’33’’ is a seminal work in experimental music, influencing fields such as sound art, acoustic ecology, and contemporary composition.

Pauline Oliveros and Deep Listening¶

Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) created the Deep Listening practice, emphasising sonic awareness as heightened attention to sound and its context. Her Sonic Meditations is a collection of text-based instructions (1971) guiding groups in listening and sound-making exercises, fostering communal awareness and creativity. Bye Bye Butterfly (1965) was an early electronic composition blending live feedback and tape delay, reflecting on the transformation of sound and memory.

Throughout her long career, Oliveros made numerous performances exploring acoustic space and group interaction. Oliveros’s work encourages active, inclusive listening and has influenced contemporary sound art, music therapy, and community music practices.

Yoko Ono and Experimental Listening¶

Yoko Ono (1933–) is a pioneering artist and composer whose work often challenges conventional boundaries between sound, performance, and audience participation. Her Instruction Pieces, such as those in Grapefruit (1964), invite listeners and performers to engage with sound and silence in imaginative, conceptual ways. Ono’s approach emphasises the creative act of listening, encouraging audiences to perceive everyday sounds as art and to reflect on the relationship between sound, environment, and intention.

Alvin Lucier and “I am sitting in a room”¶

Alvin Lucier (1931–2021) was an American composer known for his experimental works exploring acoustic phenomena and the perception of sound. His iconic piece, I am sitting in a room (1969), is a landmark in sound art and acoustic ecology. In this work, Lucier records himself reading a text describing the process: he is sitting in a room, recording his voice, and repeatedly plays back and rerecords the tape. With each iteration, the room’s resonant frequencies reinforce themselves, gradually transforming the speech into pure tones shaped by the space’s acoustics. Eventually, the words become unintelligible, replaced by the sonic “fingerprint” of the room.

Norwegian artists and practitioners¶

Norway has a vibrant community of artists and researchers working with soundscapes, listening practices, acoustic ecology, and electroacoustic composition:

Britt Pernille Frøholm (1974–): Composer and performer exploring acoustic ecology and soundscape composition in Norwegian landscapes.

Espen Sommer Eide (1972–): Artist and musician working with field recordings, sound installations, and listening walks.

Jana Winderen (1965–): Sound artist whose field recordings and installations focus on underwater and natural sound environments.

Maja S. K. Ratkje (1973–): Composer and performer integrating environmental sounds and experimental listening in her works.

Natasha Barrett (1972–): Composer and sound artist specialising in spatial audio, immersive sound installations, and electroacoustic composition.

These practitioners have contributed to both artistic and academic developments in the field, often collaborating across disciplines to deepen our understanding of sound and listening in Norwegian contexts.

Capturing sound¶

Let us conclude this week by summarising how we can capture and represent sound. This can include written descriptions, visual representations, and audio recordings.

Writing about sound¶

Writing about sound is a way to translate auditory experiences into language. It is always good to start with some contextual notes, such as recording the time, location, and circumstances in which the sound occurred. Then you can capture your emotional or sensory response to the sound, noting how it affected your mood or perception.

A more analytical approach involves breaking the sound down into components and discussing its structure or function. The DIP TiPS approach suggests describing sounds according to the following attributes:

| Attribute | Description | Range/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Duration | Length of sound | Short – Long |

| Intensity | Loudness | Soft – Loud |

| Pitch | Frequency | Low – High |

| Timbre | Sound quality | Pure – Noisy |

| Pattern | Repetition/Order | Regular – Irregular |

| Speed | Tempo | Slow – Fast |

At first, it may be challenging to use such descriptions systematically. However, a structured approach helps compare sounds (and soundscapes).

Drawing sounds¶

Words may not always be the best way to represent sounds you hear. Sometimes, drawing sounds can be more efficient. People use different approaches; some draw timelines with “waveforms” that represent the amplitude and shape of a sound over time. Others use shapes, lines, and colours to depict qualities such as loudness, pitch, or texture.

During soundwalking, it may help to create maps or diagrams showing the spatial distribution of sounds in an environment. Such visual representations can reveal patterns and relationships that are difficult to express in words and are helpful in both artistic and scientific contexts.

Recording sounds¶

Recording sounds is the most direct and “objective” way to capture and preserve sonic events. There are numerous ways to record sounds. Remember that the best sound recorder is the one you have at hand and use. In many cases, a mobile phone can do the job, particularly if you set it to record with high quality.

While single-microphone recordings are fine for capturing sound objects, stereo or ambisonics recorders are more popular for capturing soundscapes. The latter captures the whole soundfield so that it can be recreated in “surround”.

Regardless of the devices used, pay attention to microphone placement, levels, and background noise to ensure clear recordings. It also helps to keep notes about the recording context, including date, time, location, and any relevant observations. That makes it easier to organise recordings for future use and for sharing with others.

Questions¶

Explain the concepts of keynote sounds, signals, and soundmarks as defined by R. Murray Schafer.

What is the practice of soundwalking, and how did Hildegard Westerkamp contribute to its development?

Describe Pierre Schaeffer’s concept of the sound object and the three core types he identified.

Provide an example of schizophonia and explain how separating sound from its source can change listener perception.

How does acousmatic or reduced listening change the relationship between sound, source, and listener interpretation?

- Godøy, R. I., Jensenius, A. R., & Nymoen, K. (2010). Chunking in Music by Coarticulation. Acta Acustica United with Acustica, 96(4), 690–700. 10.3813/aaa.918323

- Jensenius, A. R. (2022). Sound Actions: Conceptualizing Musical Instruments. The MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/14220.001.0001