Sensing sound and music¶

This course is called “Sensing Sound and Music”. But what does that mean? And what do those three words mean on their own?

Sound and music are fundamental to human experience, serving as both a medium of communication and a form of artistic expression. Sound is a physical phenomenon characterised by vibrations that travel through a medium, while music is an organised arrangement of sounds that evoke emotional, cognitive, and cultural responses. Humans sense sound through our auditory system, but as we will discuss throughout the course, also through our bodies. Exactly how we “sense” music is still one of the core questions of both musicology at large and music psychology more specifically. It is also of interest in music technology.

Research in music psychology examines how humans perceive and process sound, including pitch, rhythm, timbre, and harmony. Technological advancements, such as digital audio workstations and sound synthesis, have expanded the boundaries of music creation and analysis, enabling new forms of artistic exploration.

An interdisciplinary approach¶

This course aims to be interdisciplinary, drawing on methods, theories, and perspectives from multiple academic fields to address complex questions about sound and music. Interdisciplinarity goes beyond simply combining knowledge from different areas; in this case, it involves combining knowledge from musicology, psychology, and technology. The idea is that by approaching sound and music from these varied viewpoints, we gain a richer understanding of how humans perceive, experience, and create music, as well as how technology can enhance and transform these processes.

Some etymology¶

Etymology is the scientific study of the origin and history of words and how their meanings and forms have changed over time. The word “etymology” is itself derived from the Ancient Greek words étymon, meaning “true sense or sense of a truth”, and the suffix logia, denoting “the study or logic of”. Similarly, we can investigate the three disciplines in question:

Musicology: The term “musicology” comes from the Greek words mousikē (music) and logia (study). It is the scholarly study of music, covering its history, theory, and cultural context. Musicologists analyse how music is composed, performed, and understood across different societies and eras.

Psychology: “Psychology” is derived from the Greek psyche (soul, mind) and logia (study). It is the scientific study of the mind and behaviour. Music psychologists explore how people perceive, process, and respond to music emotionally and cognitively.

Technology: The word “technology” originates from the Greek techne (art, craft, skill) and logia (study). Technology refers to the tools, techniques, and systems humans create to solve problems or enhance capabilities. Music technology includes the development and studies of instruments, recording devices, software, and other innovations that help create, analyse, or experience music.

By the end of the course, you will have learned some of the basic terminology, theories, and methods used in all these directions.

Differences between disciplinarities¶

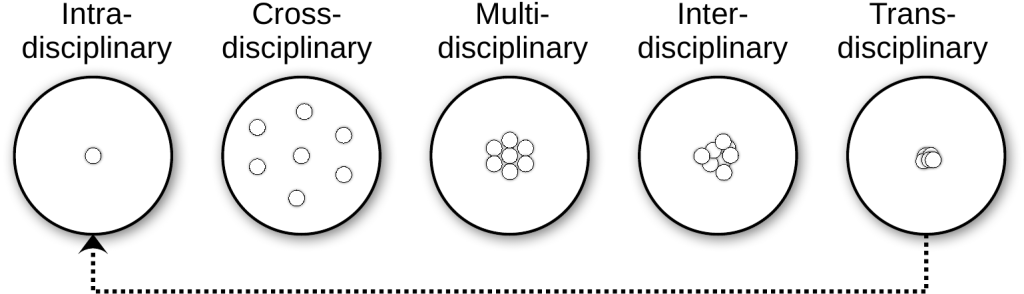

When approaching different disciplines, it is vital to understand how they interact. Many people call all sorts of collaboration between disciplines “interdisciplinarity”. However, there are some differences, highlighted in this figure:

An illustration of different levels of disciplinarity (Jensenius, 2022).

Intradisciplinary work stays within a single discipline, while crossdisciplinary approaches view one discipline from the perspective of another. Multidisciplinary collaboration involves people from different disciplines working together, each drawing on their own expertise. Interdisciplinary work integrates knowledge and methods from multiple disciplines, synthesising approaches for a deeper understanding. Transdisciplinary approaches go further, creating unified intellectual frameworks that transcend individual disciplinary boundaries.

One approach is not better than another, and many researchers may take on different roles depending on the project type. Still, it is helpful to consider these differences as we approach each discipline and look at how they combine theories and methods.

Concepts, theories, methods¶

An academic discipline is generally characterised by a distinct set of concepts, theories, and methods that guide inquiry and knowledge production within a particular field. All disciplines have established traditions, specialised terminology, and recognised standards for evaluating research and scholarship. They often possess dedicated journals, conferences, and professional organisations that foster communication and development among practitioners. The boundaries of a discipline are shaped by its historical evolution, core questions, and the types of problems it seeks to address, providing a framework for systematic study and advancement of understanding.

In our case, each of the three involved disciplines (musicology, psychology, and technology) brings its own theories and methods. Generally speaking, musicology uses analysis, historiography, and ethnography; psychology employs experiments and surveys; and technology relies on engineering and computational modelling. However, once you begin reading the research literature and tracing the historical developments of the fields, you realise that none of them have developed along a straight path. And it becomes even more complex when they are mixed together.

Music psychology and technology¶

Most people are pretty unfamiliar with music psychology and technology as academic disciplines. Children typically learn some fundamentals of musicology in school, including basic music theory (including notation) and music history. Let us consider some of the fundamentals of each discipline.

Fundamentals of music psychology¶

Music psychology focuses on understanding how humans perceive, process, and respond to sound and music. This includes exploring topics such as:

Perception: How the auditory system and brain transform acoustic signals into musical attributes: pitch, loudness, timbre, rhythm, and spatial location.

Cognition: Higher‑level mental processes for understanding music: memory, expectation, pattern and structure recognition, attention, and segmentation.

Emotion: How music evokes, communicates, and regulates affective states, including physiological responses, appraisal, and mood modulation.

Action & Behaviour: Ways music drives movement and interaction, such as motor coordination, entrainment, performance practice, dance, and social bonding.

Development & Learning: Acquisition and change of musical abilities and preferences across the lifespan, from infant sensitivity to skilled expertise and cultural learning.

These principles help us understand the universal and individual ways in which music shapes human experience, offering insights into its psychological and cultural dimensions. In this course, we will primarily investigate perception, and briefly touch on cognition and behaviour.

Music psychology is a thriving field internationally, with numerous international communities, conferences, and journals:

Conferences and Communities in Music Psychology

ESCOM (European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music): A society that organises conferences and promotes research in the cognitive sciences of music.

ICMPC (International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition): A biennial conference that brings together researchers from around the world to discuss music perception and cognition.

SMPC (Society for Music Perception and Cognition): A society that hosts conferences and fosters research on the psychological and cognitive aspects of music.

ICCMR (International Conference on Cognitive Musicology and Research): A conference focusing on the intersection of cognitive science and musicology, exploring how humans understand and interact with music.

Neuromusic: A conference dedicated to the intersection of neuroscience and music, exploring topics such as music perception, cognition, and therapy.

Journals in Music Psychology

Music Perception: A leading journal that publishes research on the perception and cognition of music, including studies on auditory processing, musical memory, and emotional responses.

Journal of New Music Research: Explores the intersection of music psychology, technology, and theory, with an emphasis on computational and experimental approaches.

Empirical Musicology Review: Publishes empirical studies on music perception, cognition, and performance, as well as reviews of current research.

Psychology of Music: Covers a wide range of topics in music psychology, including music education, therapy, and cultural studies.

Frontiers in Psychology: A general-purpose journal with a section that focuses on auditory perception, music cognition, and related neuroscience.

Music & Science: An interdisciplinary journal that publishes research on the scientific study of music, including its psychological, cultural, and technological dimensions.

Musicae Scientiae: The journal of the European Society for the Cognitive Sciences of Music, publishing research on music psychology, cognition, perception, and interdisciplinary studies.

Given its interdisciplinary nature, music psychology researchers are typically working in either musicology or psychology departments, which also often “skews” the research in one or the other direction. Researchers employed in musicology departments tend to be more focused on real-world musical experiences, what is often termed “ecological validity,” and using (more) qualitative methods. Researchers in psychology departments typically work (more) on controlled experiments and use quantitative methods.

While many researchers in music psychology may often feel “alone” in their respective departments, there are a few larger, specialised departments or research centres that focus specifically on music psychology. In these institutions, one can often see the width of the field, covering many different theoretical and methodological perspectives. RITMO is one such example.

Fundamentals of music technology¶

Music technology involves both creating, using, and reflecting on tools and systems for creating, analysing, and manipulating sound. Key areas include:

Sound synthesis and analysis: Techniques for generating and modelling sound (additive, subtractive, FM, wavetable, granular) and for analysing its structure (time-domain, spectral analysis, resynthesis). Applied to instrument and timbre design, sound design, and research into perceptual attributes.

Digital audio recording and processing: Capture, edit, mix, and transform audio using DAWs and audio toolchains. Typical tasks include multitrack recording, editing, filtering, equalisation, dynamics processing (compression/limiting), time- and frequency-based effects (reverb, delay, pitch‑shift, time‑stretch), and mastering workflows.

Music Information Retrieval (MIR): Computational extraction of musical information from audio and symbolic data. Often implemented with machine learning and signal‑processing libraries for applications like recommendation systems, analysis, and musicology.

Interactive systems and new interfaces: Design and implementation of real‑time, responsive systems for performance and interaction. Covers sensors and controllers, expressive mappings, communication protocols (MIDI, OSC), and platforms/frameworks for prototyping. Used in digital instruments, live coding, installations, and adaptive performance systems.

Music technology researchers are typically employed in departments of musicology, engineering, or informatics. Many of them combine creative and artistic exploration with scientific inquiry.

There are also many international journals, communities, and annual conferences in music technology:

Conferences and Communities in Music Technology

ICMC (International Computer Music Conference): The oldest conference in the field focuses on computer music research, composition, and performance, bringing together artists, scientists, and technologists.

SMC (Sound and Music Computing Conference): Covers topics in sound and music computing, including audio analysis, synthesis, and interactive systems.

NIME (New Interfaces for Musical Expression): Explores new musical instruments and interfaces, emphasising innovation in music performance and interaction.

CMMR (Computer Music Multidisciplinary Research): Promotes multidisciplinary research in computer music, including psychology, acoustics, and engineering.

ICAD (International Conference on Auditory Display): Focuses on the use of sound to convey information, covering topics such as sonification and auditory interfaces.

DAFx (Digital Audio Effects Conference): Dedicated to research on digital audio effects, signal processing, and music technology.

ISMIR (International Society for Music Information Retrieval): Advances research in music information retrieval, including audio analysis, machine learning, and music data processing.

AES (Audio Engineering Society): An international organisation for audio engineers, hosting conferences on sound recording, processing, and reproduction.

Journals in Music Technology

Computer Music Journal: Focuses on digital audio, sound synthesis, and computer-assisted composition, providing insights into the intersection of music and technology.

Journal of the Audio Engineering Society (JAES): Covers a wide range of topics in audio engineering, including sound recording, processing, and reproduction.

Organised Sound: Explores the theory and practice of electroacoustic music and sound art, with an emphasis on innovative approaches.

Journal of New Music Research: Publishes research on music technology, computational musicology, and the development of new musical tools and systems.

Leonardo Music Journal: Focuses on the creative use of technology in music and sound art, highlighting experimental and interdisciplinary work.

Frontiers in Digital Humanities: Digital Musicology: Explores the application of digital tools and methods to music analysis, composition, and performance.

Transactions of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval (TISMIR): Publishes research on music information retrieval, covering topics such as audio analysis, machine learning, and music data processing.

Comparing music psychology and technology¶

When comparing them, there are some essential differences between music technology and music psychology as disciplines. Music psychology is primarily a scientific field of study, focused on understanding how humans perceive, process, and respond to music through empirical research and theoretical frameworks. Its methods are rooted in experimental design, data analysis, and psychological theory, aiming to uncover universal principles and individual variations in musical experience.

Music technology, on the other hand, spans several domains: science, art, design, and engineering. It encompasses scientific research into sound and audio processing, artistic exploration through composition and performance, design of musical instruments and interfaces, and engineering of hardware and software systems. Music technologists may work on developing new tools for music creation, analysing audio signals, designing interactive installations, or exploring creative possibilities in digital media. This diversity means that music technology is not limited to scientific inquiry but also includes creative practice, technical innovation, and user-centred design.

At the University of Oslo, we have a long tradition of combining music psychology and technology. The logic behind this is that advanced technologies can help psychological inquiry, and psychological insights can impact the development and use of new technologies. And both disciplines can help us better understand music as a whole.

Listening to the world¶

After getting introduced to some of the (inter)disciplinary foundations for this course, let us go back to some basics: listening. We will spend next week’s class only on listening, but we will start with a little warm-up here. After all, listening is an essential human capacity and central to music (and psychology and technology!). However, most people do not think much about listening in daily life, except for when it is annoying. With a sound level too low, it is hard to hear what is said; with a sound level too loud, it is unpleasant and even dangerous. But why is that, and how do we talk about it in precise terms? That is what we will explore both here and later in class.

Hearing vs listening¶

Let us start by considering the difference between hearing and listening. In this context, we define hearing as the passive physiological process of detecting sound waves through the auditory system, while listening is an active cognitive process that involves interpreting and making meaning of those sounds.

In the psychology literature (including The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology), you will find references to several different types of hearing and listening:

Passive hearing: This occurs when sounds are registered by the ears and processed by the brain without conscious attention. For example, background noise in a café or the hum of an air conditioner.

Selective hearing: The ability to focus on specific sounds or voices while ignoring others, such as following a conversation in a noisy environment (also known as the cocktail party effect).

Active listening: Engaging attention and intention to understand, analyse, or respond to sounds or speech. This is essential in music appreciation, communication, and learning.

Critical listening: Evaluating and analysing sound quality, musical structure, or meaning, often used in music production, performance, or academic study.

Empathetic listening: Focusing on the emotional content and intent behind sounds or speech, important in social interactions and therapeutic contexts.

It is important to note that the mechanisms underlying these approaches to hearing and listening are still actively under investigation. There are many—sometimes diverging—opinions about them, their differences, and how they overlap or connect. In any case, understanding these distinctions helps clarify how we interact with sound and music, moving from automatic sensory processing to deeper engagement and interpretation.

Embodied music cognition¶

The approach to human psychology presented in this book is not neutral (not that any other book is that, either, even if it pretends to be). It is grounded in the tradition of embodied music cognition, emphasising the role of the body in musical experience. Although he did not invent the term, it became popularised after Marc Leman wrote a book with the same name (Leman 2007).

Embodied music cognition was seen as radical at first, but has become more mainstream over the years. Several researchers at the University of Oslo—with Rolf Inge Godøy in front—have been active in developing this branch of research over the last decades. The approach has been foundational to the studies of music-related body motion in the fourMs Lab and is also at the core of many activities at RITMO.

The core idea of embodied music cognition is that both the production and perception of music involve integrating sensory, motor, and emotional dimensions. To paraphrase the father of ecological psychology, James Gibson, you explore the world with eyes in a head on a body that moves around. He was mainly interested in visual perception, but his ideas have inspired similar thinking about other senses.

A different entry point to a similar idea is the concept of musicking. This term was popularised by musicologist Christopher Small, who argued that music is best understood as a verb—to music—not a noun (Small 1997). Music is not an object or a finished product (like a song or a score), but rather an activity: something people do. When a band plays a concert, the musicians, the dancers, the audience, the sound engineers, and even the people selling tickets and cleaning the hall are all engaged in musicking. The music exists not just in the notes played, but in the shared experience and interaction.

Researchers in music education and therapy have embraced the musicking concept because it allows them to think of music not as a thing but as a social activity. This implies that you do not study “the music” but instead explore the complexity of musical interactions, from the role of gestures in musical performance to how perceivers synchronise their bodies to a musical beat. By engaging the body, embodied music cognition provides a holistic framework for studying how music is experienced and understood.

Multimodality¶

The French composer Edgard Varèse, who famously argued that “music is organised sound” and advocated treating noise and timbre as primary compositional resources. Varèse’s definition of music was important in expanding the idea of music beyond traditional melody or harmony, positing that music is any sound intentionally shaped and structured over time.

In this course, however, we will expand on the idea of music. This is based on an acknowledgement of music as inherently multimodal, meaning that we—both humans and other animals—use multiple sensory modalities in the perception and understanding of the world.

The primary human senses, their associated sensory modalities, and the organs involved in each

| Sense | Modality | Human Organ(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing | Auditory | Ears |

| Sight | Visual | Eyes |

| Touch | Tactile | Skin, Hands |

| Taste | Gustatory | Tongue, Mouth |

| Smell | Olfactory | Nose |

| Balance | Vestibular | Inner Ear |

| Proprioception | Kinesthetic | Muscles, Joints |

From a psychological perspective, multimodality emphasises how the brain combines information from these different sensory channels to create a cohesive experience. In the context of music cognition, this could involve the interplay between auditory and motor systems, such as how visual cues from a performer influence sound perception or how physical gestures enhance musical expression and understanding. However, the other senses are also involved. Touch provides tactile feedback for instrumentalists and singers; proprioception and balance help musicians coordinate motion and posture, especially in dance or performance; smell or taste can contribute to the emotional context and memory of musical events.

Most people agree that sound is a core component of music, yet there are notable examples of musicians and composers who have created and performed music despite significant hearing loss. Ludwig van Beethoven, one of the most influential composers in Western music history, continued to compose groundbreaking works even after becoming profoundly deaf. This was possible by relying on other senses, such as vision and touch.

In more recent times, percussionist Evelyn Glennie has demonstrated that musical experience and expression are not limited by the ability to hear sound through the auditory system. Glennie, who lost most of her hearing by the age of twelve, developed unique techniques to sense vibrations through her body, allowing her to perform and interpret music:

Action and Perception¶

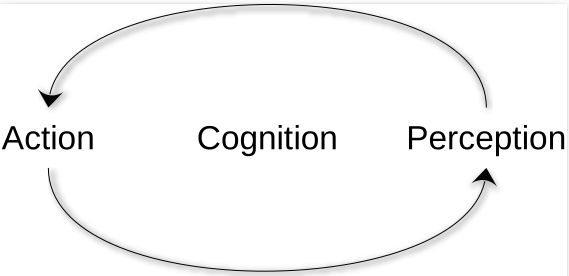

The last concept we will introduce this week is the action–perception loop. The idea of embodied cognition, in general, is that we sense through action and act through sensing. In music, the action-perception loop is evident in activities such as playing an instrument, where sensory feedback informs motor actions, and vice versa. For example, a pianist adjusts their touch in response to the sound they produce, creating a continuous cycle of interaction.

The action–perception loop is at the core of embodied music cognition.

Eric Clarke uses the action–perception loop as core to his thinking about ecological listening. He bridges psychology, musicology, and acoustic ecology, offering insights into how humans engage with sound in their lived experience. In his influential book Ways of Listening, he argues for three different listening modes:

Direct perception: Listeners perceive sounds in relation to their environment without needing extensive cognitive processing.

Affordances: Sounds provide cues about actions or interactions possible within a given environment.

Contextual listening: The meaning of sounds is shaped by their environmental and situational context.

He also notes that we often hear sounds as “the sound of” something, for example, “the sound of a guitar” or “the sound of a scream.” This source‑based listening fits neatly with Clarke’s three modes: identifying the source aligns with direct perception, recognising possible interactions links to affordances, and interpreting situational meaning is part of contextual listening. In short, attributing sounds to objects or events is one common way we make sense of auditory experience, and it will be one of several listening perspectives we examine next week.

Questions¶

What are the main differences between musicology, psychology, and technology as academic disciplines?

How can interdisciplinarity enhance our understanding of sound and music compared to single-discipline approaches?

What is the distinction between hearing and listening, and why does it matter when studying music?

How does embodied music cognition explain relationships between physical motion and musical experiences?

What is the action-perception loop, and how does it manifest in musical activities?

- Jensenius, A. R. (2022). Sound Actions: Conceptualizing Musical Instruments. The MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/14220.001.0001

- Hallam, S., Cross, I., & Thaut, M. (Eds.). (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Music Psychology, Second Edition. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198722946.001.0001

- Leman, M. (2007). Embodied Music Cognition and Mediation Technology. The MIT Press. 10.7551/mitpress/7476.001.0001

- Small, C. (1999). Musicking — the meanings of performing and listening. A lecture. Music Education Research, 1(1), 9–22. 10.1080/1461380990010102

- Clarke, E. F. (2005). Ways of Listening. Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195151947.001.0001